A team of astrophysicists at the University of Portsmouth have created the largest ever map of cosmic voids and superclusters in the Universe, which helps solve a long-standing cosmological mystery.

The map of the positions of voids – large empty spaces which contain relatively few galaxies – and superclusters – huge regions with many more galaxies than normal – can be used to measure the effect of dark energy `stretching’ the Universe.

The results confirm the predictions of Einstein’s theory of gravity.

Lead author Dr Seshadri Nadathur from the University’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation said: “We used a new technique to make a very precise measurement of the effect that these structures have on photons from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) – light left over from shortly after the Big Bang – passing through them.

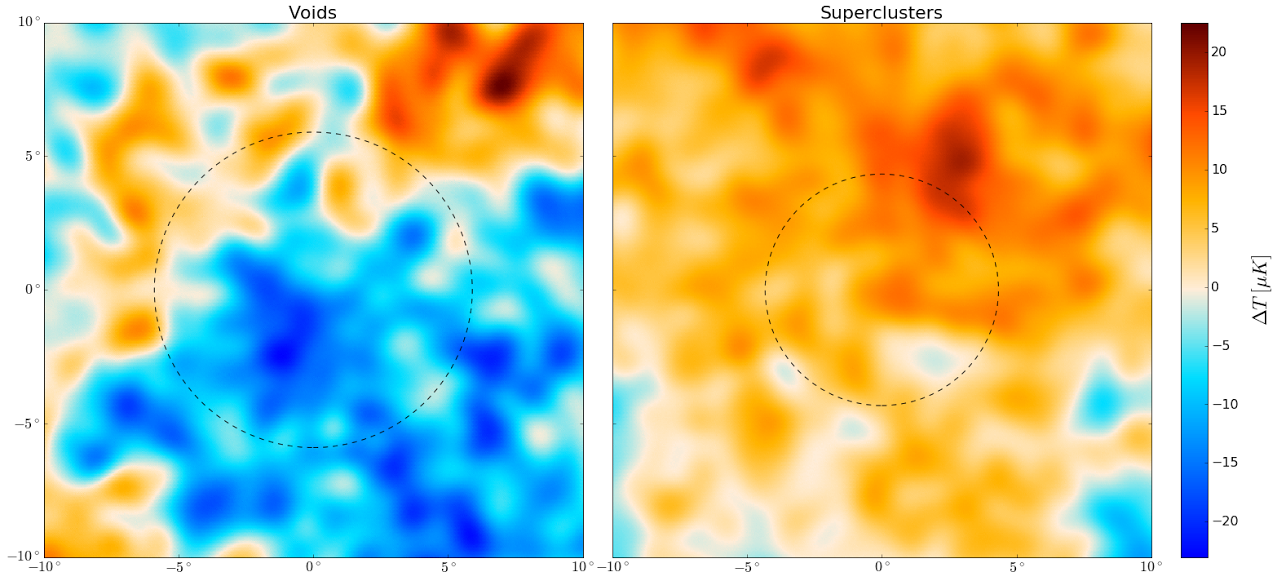

The effect of voids and superclusters seen in patches of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Photons of the CMB that have travelled through void regions on average appear slightly colder than average (left panel), and those coming from supercluster regions appear slightly hotter (right panel). The colour scale shows the temperature differences, with blue being coldest and red hottest. The circles show the regions over which the effect is expected to be most important.

“Light from the CMB travels through such voids and superclusters on its way to us. According to Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, the stretching effect of dark energy causes a tiny change in the temperature of CMB light depending on where it came from. Photons of light travelling through voids should appear slightly colder than normal and those arriving from superclusters should appear slightly hotter.

“This is known as the integrated Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect.

“When this effect was studied by astronomers at the University of Hawai’i in 2008 using an older catalogue of voids and superclusters, the effect seemed to be five times bigger than predicted. This has been puzzling scientists for a long time, so we looked at it again with new data.”

To create the map of voids and superclusters, the Portsmouth team used more than three-quarters of a million galaxies identified by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. This gave them a catalogue of structures more than 300 times bigger than the one previously used.

The scientists then used large computer simulations of the Universe to predict the size of the ISW effect. Because the effect is so small, the team had to develop a powerful new statistical technique to be able to measure it the CMB data.

They applied this technique to CMB data from the Planck satellite, and were able to make a very precise measurement of the ISW effect of the voids and superclusters. Unlike in the previous work, they found that the new result agreed extremely well with predictions using Einstein’s gravity.

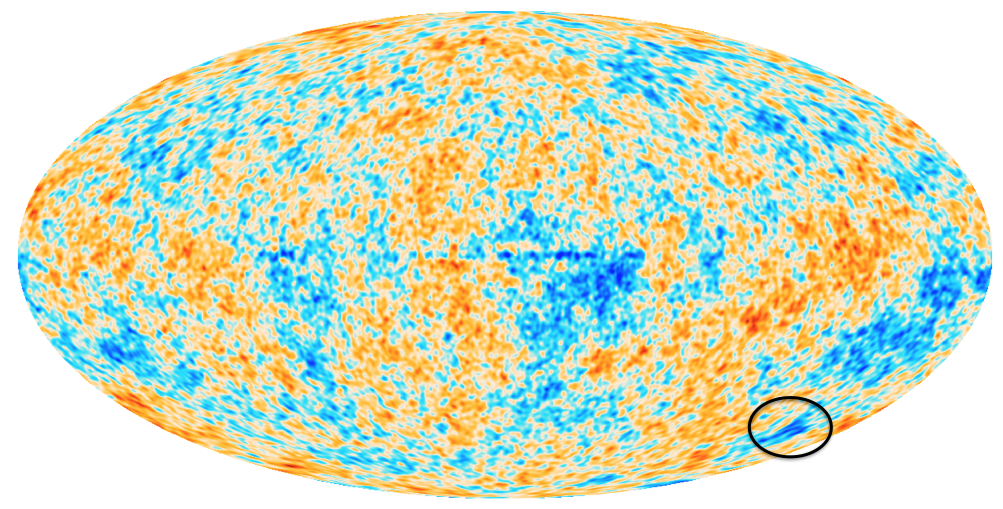

The cosmic microwave background temperature fluctuations, with the unusual ‘Cold Spot’ feature circled at the lower right.

Dr Nadathur said: “Our results resolve one long-standing cosmological puzzle, but doing so has deepened the mystery of a very unusual ‘Cold Spot’ in the CMB.

“It has been suggested that the Cold Spot could be due to the ISW effect of a gigantic ‘supervoid’ which has been seen in that region of the sky. But if Einstein’s gravity is correct, the supervoid isn’t big enough to explain the Cold Spot.

“It was thought that there was some exotic gravitational effect contradicting Einstein which would simultaneously explain both the Cold Spot and the unusual ISW results from Hawai’i. But this possibility has been set aside by our new measurement – and so the Cold Spot mystery remains unexplained.”

The paper is published this week in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

From the University of Portsmouth Press Office