An international team of scientists, including from the UK’s University of Portsmouth, today released the first in a series of dark matter maps of the cosmos.

The maps, created with one of the world’s most powerful digital cameras, are the largest contiguous maps created at this level of detail, and will improve our understanding of dark matter’s role in the formation of galaxies.

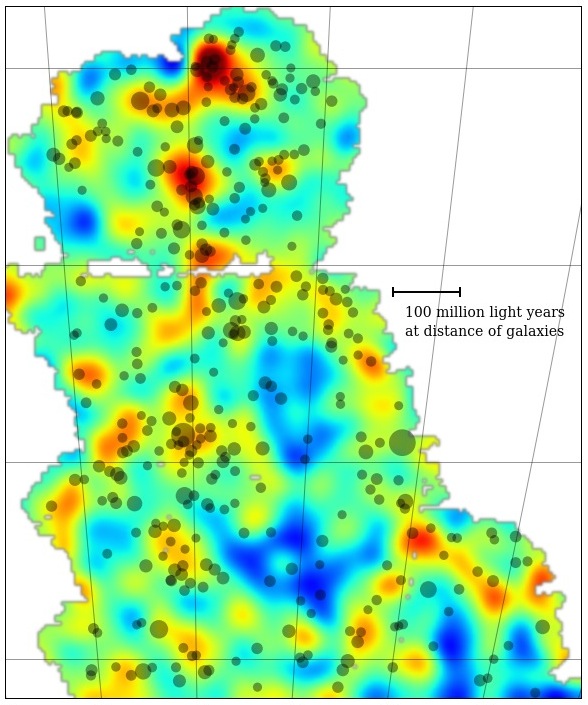

This is the first Dark Energy Survey map to trace the detailed distribution of dark matter across a large area of sky. The colour represents projected mass density. Yellow and red are regions with more dense matter. The dark matter maps conform to the current picture of mass distribution in the universe where large filaments of matter align with galaxies and clusters of galaxies. The clusters of galaxies are shown by the grey dots in the map — bigger dots represent larger clusters. This map covers three percent of the area of sky that DES will eventually document over its five-year mission.

Analysis of the clumpiness of the dark matter in the maps will also allow those working on the Dark Energy Survey to probe the nature of the mysterious dark energy, believed to be causing the expansion of the universe to speed up.

Publication coincides with the start of the American Physical Society meeting in Baltimore, which includes many Dark Energy Survey talks and posters over two days, and is synchronised with a tranche of research papers publicly released on the arXiv.org e-Print server today.

Dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up roughly a quarter of the universe, is invisible to even the most sensitive astronomical instruments because it does not emit or block light. But its effects can be seen using a technique called gravitational lensing – studying the distortion that occurs when the gravitational pull of dark matter bends light around distant galaxies. Understanding the role of dark matter is part of the research programme to quantify the role of dark energy, which is the ultimate goal of the survey.

David Bacon, at the University of Portsmouth’s Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, said: “Using the gravitational lensing technique, we can see the dark matter filling our Universe. We see it by how this invisible material bends and distorts light as it passes through. We can now make maps of the dark matter and see how it clumps together, providing an insight into the cosmic web of matter including clusters and the filamentary structure that joins them.”

The new maps were created using data captured by the 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera in Chile.

Dr Bacon said: “The camera is one of the most powerful cameras in the world, collecting data nearly ten times faster than previous machines. This allows us to stare deeper into space and see the effects of dark matter and dark energy with greater clarity. Ironically, although these dark entities make up 96 per cent of our universe, seeing them is hard and requires vast amounts of data.”

The researchers are two years into a five-year programme as part of their work on the Dark Energy Survey.

The dark matter maps released today cover only about three per cent of the area of sky the Dark Energy Survey team will document over its mission. As scientists expand their search, they’ll be able to better test current cosmological theories by comparing the amounts of dark and visible matter.

Those theories suggest that since there is much more dark matter in the universe than visible matter, galaxies will form where there are large concentrations of dark matter. So far, the DES analysis backs this up. The maps show large filaments of matter, along which visible galaxies and galaxy clusters lie, and cosmic voids with very few galaxies.

Follow-up studies of some of the enormous filaments and voids, and the enormous volume of data, collected throughout the survey will reveal more about this interplay of mass and light.

The Dark Energy Survey analysis is available here.

Originally posted by the University Press Office